“What language should she learn next?” my niece’s parents mused.

The year was 2012. My niece, Jing Jing, had just turned 4, and the question referred to what would be her third language after Mandarin, her native tongue, and English, a requisite for the upwardly mobile middle class in China.

Looking through the WeChat video screen at my niece fumbling with a teddy bear in the background, I gave the most preposterous answer I could think of.

“C++,” I quipped.

My aunt and uncle beamed.

Today, I can’t help but feel a twinge of responsibility when I video chat with 13-year-old Jing. Jing’s room overflows with trophies from Scratch coding competitions, co-curricular math workbooks, and mechanical machinations from robotics summer camps. She is a coding whiz kid, a regional math champion, a budding programmer fluent in Python, Java, and soon JavaScript. She is readying herself to compete in the global workforce. She is prepared.

But is she?

In 2018, the World Economic Forum (WEF) estimated that “65% of children entering primary school today will ultimately end up working in completely new job types that don’t yet exist.”

What good does knowing JavaScript do when those jobs might not exist? Those skills might get her a job today, but what about in 2030 when she enters the workforce? What about tomorrow?

The World Economic Forum estimates that 65% of kids entering elementary school today will end up working in jobs that don’t yet exist.

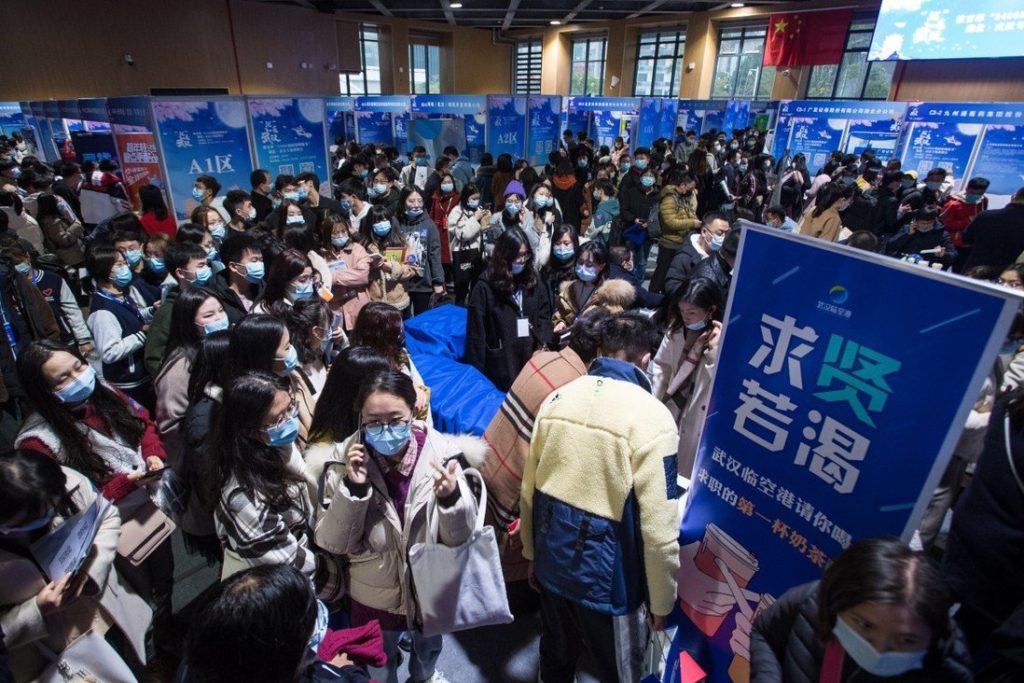

My Chinese relatives’ anxiety is understandable. In a country of 1.39 billion people, where the number of students enrolled in degree programs grew five-fold in the span of 14 years, the job market is tightening. White-collar job growth has tapered off while wages stagnate. Postsecondary degrees don’t hold the same weight. Beijing even cracked down on wildly popular after-school training services this year, citing unscrupulous business practices that prey on the anxieties of the middle class.

Class anxiety, to be sure, has always existed. It isn’t exclusive to China, either.

What’s new is the growing body of research that points to how automation and globalization will upend the nature of work, the types of work available to humans, and how people and machines work together.

While business and government are figuring out the best steps forward for society, what’s a young person today to do?

In its Future of Jobs Report, the World Economic Forum hails a “Fourth Industrial Revolution” in which new job categories emerge, displacing others, and the skills needed to thrive in all occupations adapt alongside their industries. Where will people work? How will people work? What skills will they need to succeed in the jobs of the future?

The pandemic has already shown us one answer to the first question: anywhere, if your job (and your CEO) allows for it.

My employer, Autodesk, is working with cross-sector leaders to help answer the other two questions. With support from the Autodesk Foundation, we explored the unique opportunities and challenges for workers across Asia Pacific. What we found surprised us. While digitization and automation will affect all workers across sectors and geographies, some are more at risk. And while solutions abound, workers who cannot access them—especially those who don’t speak English—are most at risk of being left behind.

Autodesk is also working closely with the World Economic Forum to integrate its global skills taxonomy into our upskilling and reskilling programs for our employees and customers to ensure they can thrive long into the future.

According to the Future of Work Practice Lead at Autodesk, Kate McElligott, “In the future, workers will be increasingly hired based on their skills and expertise rather than pedigree or prior experience. As a result, new systems are needed to validate knowledge in increasingly nimble and creative ways—which is both exciting and disruptive to the status quo.”

“Workers will be increasingly hired based on skills and expertise rather than pedigree. New systems are needed to validate knowledge in increasingly nimble and creative ways.”

Kate McElligott, Future of Work Practice Lead at Autodesk

Systemic change takes time. But in the short term, workers can focus on acquiring the most in-demand skills that don’t require formal education. According to WEF, active learning, resilience, stress tolerance, and flexibility are increasingly in demand, with critical thinking and problem solving topping the list of skills employers believe will grow in the next five years. Combine these with the right technical skills and students are well placed to succeed.

While businesses and governments are figuring out the best steps forward for society, what’s a young person today to do? Here are the things I know to be true:

- We don’t know what the future holds. Despite the best efforts of economists, historians, statisticians, futurists, and consultants, we still can’t predict precisely what the future holds. But we can prepare kids with foundational skills.

- We need to teach foundational skills. These include the interpersonal—like teamwork, collaboration, empathy, and citizenship—and the technical—like the building blocks of innovation that can be remixed, converged, or combined to tackle old problems in new ways.

- We can start anywhere, anytime. For many, Tinkercad® software is the first step in a lifelong learning journey that begins in middle school. But we’ve seen plenty of success from educators using Tinkercad for project-based learning (PBL) in math, science, language arts, and even art classes as early as first grade.

Jaime Perkins, Director of Learning Strategies at Autodesk, stresses the importance of the “four Cs” for this age group: critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and communication. He cites Carol Dweck’s work on the psychology of success.

“In secondary education, mindsets are as important, if not more important, than toolset or skillset. What Autodesk is doing with Tinkercad has a lot to do with shaping mindsets for the future.”

Jaime Perkins, Director of Learning Strategies at Autodesk

Remember that old saying “knowledge is power”? Let’s equalize power by lighting the path for tomorrow’s makers, designers, and creative problem solvers. Knowing how to make things allows us to do more than just consume. It allows us to create. And that’s powerful—because it means we’re not passively accepting the current state of the world: we’re actively participating to rewrite the rules, defy the odds, and shape the future.

Realizing an idea and holding it in our hands isn’t just powerful: it’s empowering. The physical world isn’t going away in the future, and neither are the opportunities for people who know how to make things. The future of work is evolving, design and make are converging, and everyone deserves a fair shot at playing in the game. We need more kids growing up with the skills, experience, and confidence to know that they can create a better world.

Knowing how to make things is powerful because it means we’re not passively accepting the state of the world: we’re actively rewriting the rules.

Sure, machines are getting smarter by the day (I see you, Alexa, Siri, Waymo, and generative design). But as far as I’m concerned, the most important intelligence isn’t artificial: it’s in us. Anyone can make anything when equipped with the right tools, training, and opportunities.

That’s why Autodesk is committed to inspiring the next generation to imagine, design, and make a better world. With Tinkercad, kids can go from manipulating basic shapes on a work plane to building light-up skyscrapers programmed in 3D. They can even realize their designs in the physical world with access to 3D printers, breadboards, and circuits—tools that are becoming more ubiquitous in schools and makerspaces around the world. And once students are ready to explore pathways to careers in manufacturing, construction, or infrastructure, high school curricula like Project Lead The Way Engineering, professional tools like Autodesk® Fusion 360® technology, and co-curricular competitions like F1 in Schools are ready to meet kids at the intersection of their skills and passions.

Machines are getting smarter by the day. But the most important intelligence isn’t artificial: it’s in us.

Business and industry will always demand innovators who create solutions to our toughest problems as the world demands more, faster, cheaper, and better. But the point isn’t whether our kids should learn JavaScript or C++ or HTML to prepare for that future. What gets lost in the conversation about kids and the future is this: Are they kind? Are they curious? Do they enjoy what they do? Will they be good stewards of our planet?

When I video chat with Jing today, she doesn’t list off the programming languages she knows, or the courses she’s taken. She doesn’t recall the specific tools or lessons taught. Instead, she remembers:

The first time she held a 3D-printed object in her hands—one she designed all by herself.

The way her teachers inspire her with inventions of the past and challenges of the future.

The length of the list of ideas she’s jotted down since learning how to make and design.

How many of those ideas she’s brought to life.

How many of those she’s yet to tackle.

Daria Zhao leads product marketing for Youth (K-12) at Autodesk, a company that makes software for people who make things. She works on products like Tinkercad, Instructables®, and Fusion 360 in education.