How a global team of 1,500 artists collaborated virtually on “The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power”

Diana Colella, executive vice president of Media & Entertainment at Autodesk, sat with Ron Ames, a producer on season one of The Amazon Prime series “The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power,” Ramsey Avery, series production designer, and Hugh Calveley, Flow Capture (formerly Moxion) co-founder at NAB 2023 to talk about building and executing a new virtualized approach to episodic television production on a global scale.

The series is set thousands of years before the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, in the Second Age of Middle-earth. The production ecosystem behind the series, however, leapt far ahead, as one of the first to use cloud production from start to finish.

The massive production had 786 hours of 4K camera dailies that became eight hours of theatrical material. 1,500 artists from 12 vendors on five continents created 9,000 VFX shots, post-production color grading and sound, using an entirely cloud-based workflow specified and designed by Amazon Studios with Autodesk Flow Production Tracking (formerly ShotGrid) and Autodesk Flow Capture (formerly Moxion) at its core.

“This was filmmaking on an industrial scale — the equivalent of doing four features,” said Ames, who was responsible for technical departments from camera capture to exhibition. “We knew that traditional methodologies weren’t going to work.” Given that, the team started devising a workflow that could handle the massive amounts of data and connect the global team.

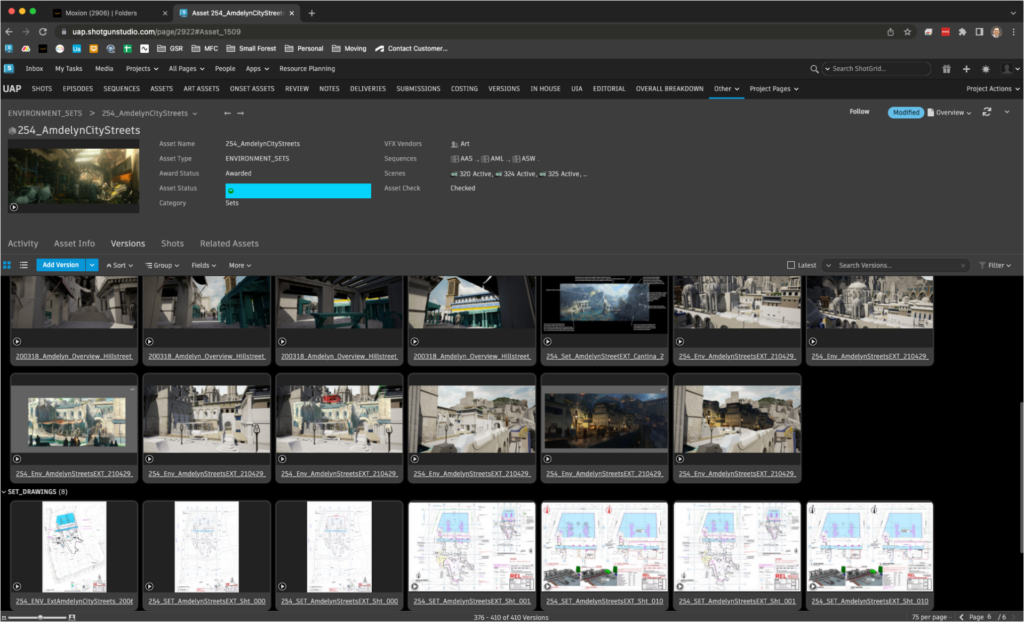

When Colella asked how they approached the infrastructure challenges, Ames said, “We knew two things: One, that we were going to use Flow Production Tracking for visual effects tracking to create a vendor-based virtual facility. Two, this had to be a cloud-based production. Since it was one of the first fully cloud-based productions of this scale, the tools weren’t fully built, but we just sprung ahead.”

The building blocks of data and creative collaboration

Ames headed to New Zealand to build infrastructure along with Calveley, who had recently launched Flow Capture (formerly Moxion). Autodesk Flow Capture’s solutions capture footage from cameras and send it to the cloud, enabling production and post teams to collaborate seamlessly across sets and locations. It became an overnight success when the pandemic drove a shift to remote production. “People realized that the cloud was not just a place to store and retrieve things, but a place where whole productions could exist and progress. It helped people re-imagine how productions could be with people participating virtually,” said Calveley.

The team deployed a 500 TB Pixtor server on-prem at Auckland Film Studios, with direct connectivity to AWS via dual 10 GB fiber. They connected the two local offices with dark fiber so anyone in either office could see the exact same material.

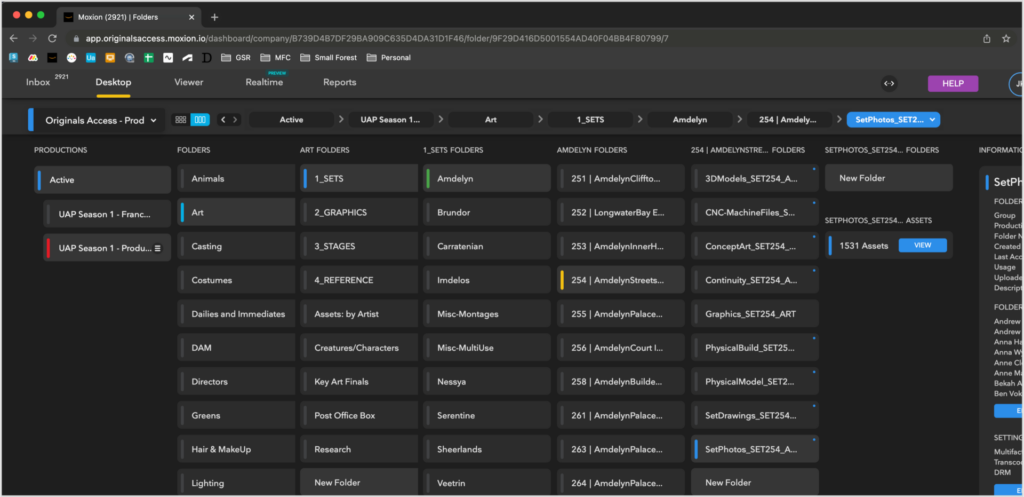

With the infrastructure now in place, the task turned to data and creative collaboration for a massive global team. Avery said, “We had people working on five continents across nine time zones. Trying to keep track of all that data and get the information flowing cleanly was one part of the puzzle. The other was, how does communication happen and how do we work with artists who are so spread out? How do we keep the collaboration open every day?”

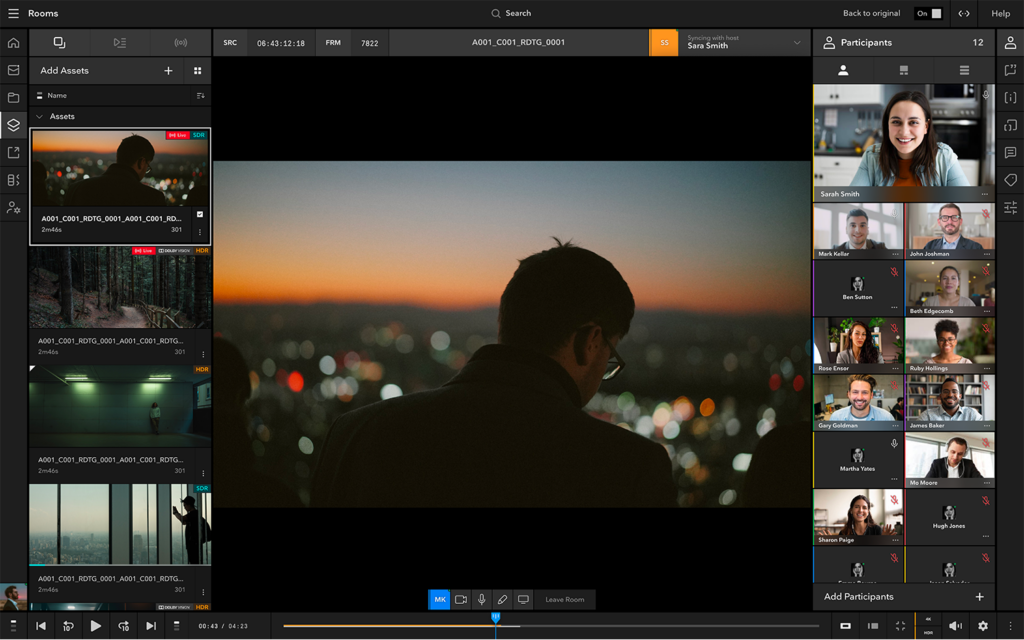

Collaboration rooms

That question sparked a brand-new capability that evolved more recently into a new Flow Capture (formerly Moxion) feature, Flow Capture Rooms. Think video conferencing inside Flow Capture, but with much more sophisticated functionality. The idea was to enable anyone at any stage of the production to communicate with anyone else, and view live streams using a common play head. It was invaluable for post-production, audio, and editorial, Ames noted. “We were editing in real time across the globe. We could show finished color in 4K.”

With Rooms, Ames said, “The art department, visual effects, editorial — really became one department that shared constantly. That created not only a collegial feeling and warmth, but the ability to solve problems together.”

New workflows bring fresh creative processes to life

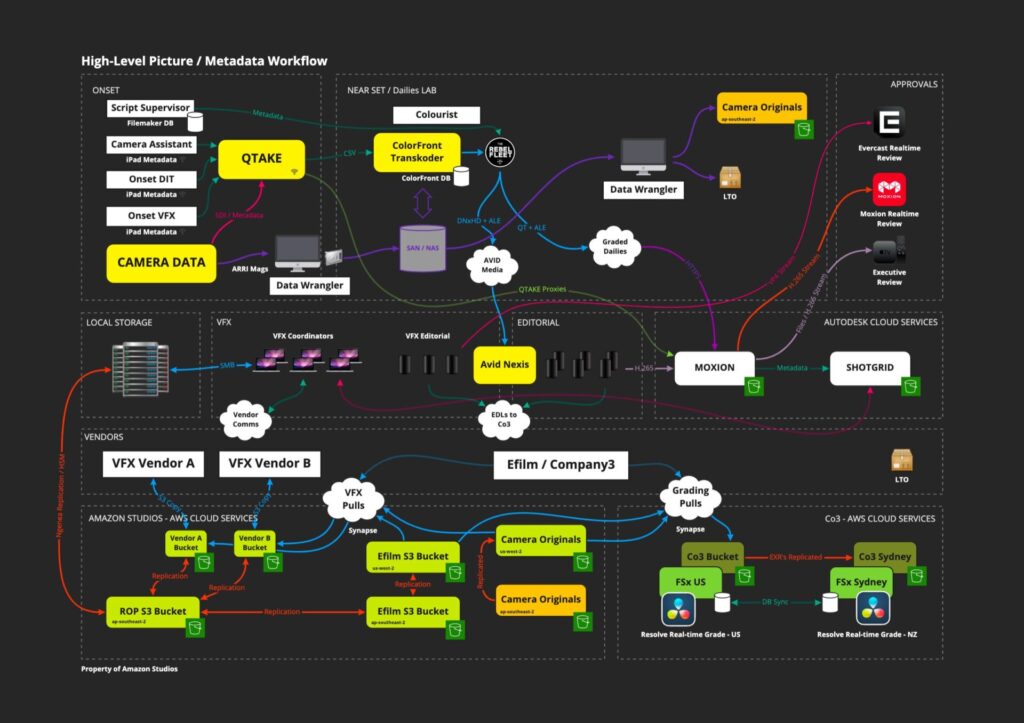

New methodologies were made possible by a camera-to-cloud on-set workflow that started with Flow Capture (formerly Moxion). Metadata was captured from the set into QTAKE, then transcoded. Proxy media and metadata went to Flow Capture for publishing and sharing and into the Flow Production Tracking (formerly ShotGrid) relational database for tracking. Camera RAW files and metadata were uploaded to AWS where RAW plates were available to artists at each vendor company worldwide to enable and accelerate iteration and delivery of finished VFX and color, and the final deliverable.

A key element of the workflow was that post-production could, having used instant dailies, reflect ‘back to set’ what they had just shot looked like in the final edit. Calveley explained, “An editor could look at what was happening on set or even VFX to make changes that would save time in the future.”

The picture/metadata workflow was complex behind the scenes to enable controlled collaboration among VFX, editing, and post data and teams, as well as costumes, casting, hair and makeup, props, lighting, directors, studio and every participant involved in the production.

The shoot also included virtual production, so teams could “see all the parts you couldn’t really see,” as Ames put it. “The actors, director, DP — they could point the camera at something that wasn’t there, but we knew precisely where it was going to be. Moving all this data around from set to set, location to location, was made possible with Flow Capture (formerly Moxion).”

Scale, speed and security

Calveley spoke to other benefits. “There was no need to pre-plan how much computation was available. You could just get it when you needed it. So, if Ron decided to upload 10,000 Harfoot images, he didn’t need to know that we had a whole lot of AWS Lambdas or Fargates ready to process it. We could just spark them up as needed and then spark them down. It only cost us while we were running it.”

Avery noted that the speed at which the production moved was on a different level. “When somebody’s doing previews, somebody else is doing storyboards, there are people building models here, people doing Maya animations over there, showrunners, writers, VFX and people trying to get things built. All of those sources and those means of ideation and creation could communicate together effectively.”

Calveley noted that a side effect of that workflow is that “people who were traditionally further down the food chain wouldn’t see something until several days later. Now they’ve got a seat at the production table.”

Since cloud production first emerged, a key concern has always been security. With Flow Capture (formerly Moxion), production could set up a watertight, single sign-on to the project in the cloud backed by built-in forensic watermarking, multi-factor authentication, highly secure data centers and digital rights management. Calveley remembers being asked, “Surely, it’s dangerous having a single passcode that can access all of this information? And my response is, ‘Would you prefer to have a thousand little, tiny locks that can be easily picked or one huge, unpickable lock which is guarded by ninjas with lasers for eyes?”

Modern moviemaking

Colella inquired how the experience of an entirely cloud-based production ecosystem impacts production — not just for this team, but overall.

The panelists spoke to the reality that studio systems have built their workflows over 50-100 years of film and television production.

“Sometimes breaking those walls is almost impossible,” Avery said. But he sees ‘modern filmmaking’ beginning to spread, with departments interconnecting around a central database and working together.

Ames noted that “probably 90% of the shows I’m currently working on have some cloud-based aspect,” prompting Colella to start a discussion around hybrid workflows, and how decisions are made about which processes to do in the cloud. Questions around whether a show is location-based or will be largely based on an LED-wall environment, whether it’s a multi-season show vs. a one-off, or whether the production would have games or other transmedia aspects are all considerations when looking at cloud production.

Ames said a “constellation of tools” is being created for cloud-based filmmaking, and that standardization on how assets are built and shared will go a long way to advancing the medium.

The learnings for future productions are many. For “Rings of Power,” the choice was clear. Calveley said, “With the scale, security requirements, and speed that was happening on this production, we couldn’t have done it any other way than in the cloud.”

Ames concluded, “We needed to have constant unity and communication at all times. That interconnection was serviced by Flow Production Tracking (formerly ShotGrid) and Flow Capture (formerly Moxion).”