Immerse yourself in Digital Domain’s epic 3D creations, discovering how they craft character design and performance to convey emotion and personality.

The 2025 Netflix film The Electric State exudes epic vibes from the scope of its story, the expanse of its landscapes, the skill of its performances, and perhaps most notably, the creative vision of its legion of 3D animated characters. More than 100 3D characters originated from VFX studios like Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), Storm Studios, and One of Us, with Digital Domain alone building 61 different characters for this big-budget film.

This was Digital Domain’s most massive 3D character undertaking yet, according to Liz Bernard, the studio’s Senior Animation Supervisor. Over the course of about two and a half years, Digital Domain tapped a production pipeline of 245 talented artists, production experts, and software specialists to deliver 58 minutes of footage, 83,795 frames in total, for this ambitious cinematic adaptation of Simon Stålenhag’s 2018 dystopian science fiction illustrated novel. Their pipeline included Autodesk Maya for 3D modeling, animation, shot modeling, and integration; the Golaem plugin for Maya for crowd character simulation, and Autodesk Flow Production Tracking for production management.

The Electric State’s story follows a teenage girl and her robot companion’s quest through an alternate timeline 1990’s United States, where excessive use of technology and human-vs.-robot wars have ravaged the countryside. The movie includes a cast of stars and was directed by Joe and Anthony Russo, best known for directing Avengers: Endgame (2019).

At SIGGRAPH 2025, Bernard presented “Heroes, Crowds, and Heart: Building Character in The Electric State,” which detailed the intricacies of Digital Domain’s hero and crowd character development for this visually stunning film. The session was part of Autodesk’s Vision Series, where studios and artists share behind-the-scenes of the year’s biggest blockbusters, and explore how AI and open, connected workflows are transforming the creative process. Before going any further, make sure to check out Digital Domain’s sizzle reel for The Electric State at the front of this video (0:30-5:35). It’s five minutes well-spent.

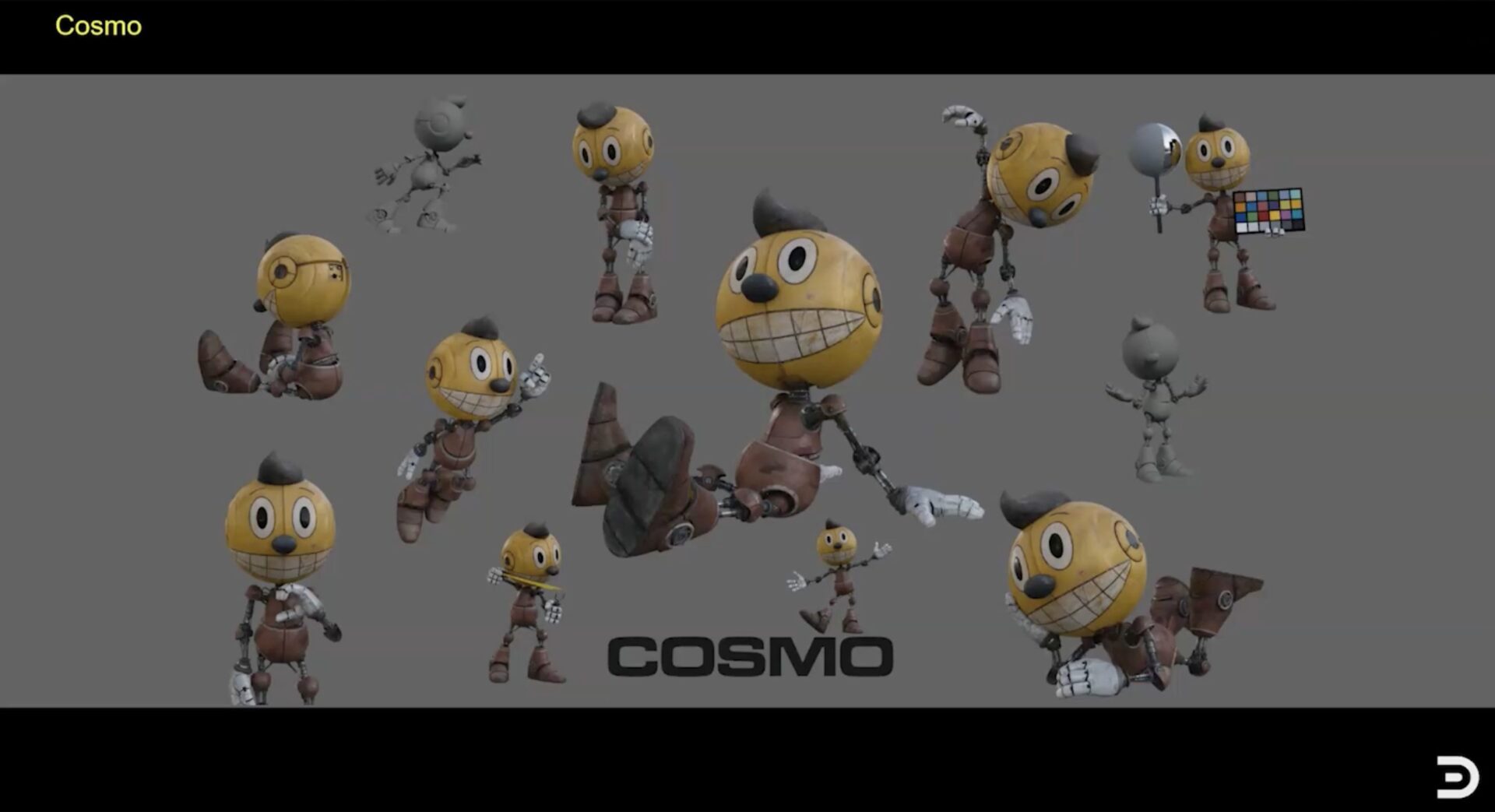

Cosmo: The Heart of the Film

With his “lollipop head,” giant permanent grin, huge feet, and big, white-gloved hands, Cosmo (07:43-11:30) is immediately recognizable as one of the key characters from Stålenhag’s book. He can’t really speak but communicates with voice recordings from a cartoon that main character Michelle watched as a child. (For example, “the solar system’s gone haywire!”) Other than that, Digital Domain was tasked with having him express himself through body language, hand posing, and head tilts. They also showed his emotional state and thought process by dimming or brightening the LED lights set deep in his eyes behind a layer of smoked glass (11:09-11:30).

“I’ve never worked with a character that had a giant freaky smile permanently painted onto his face,” Bernard says. “Getting him to emote things like pathos, sadness, determination, and depth was not so easy with a face like that staring down at you from the Maya viewport [10:11].”

With Cosmo’s odd anatomy, Digital Domain gave him a “giant clown shoe shuffle” walk (8:43-9:36) that was almost entirely hand key framed animation, rather than motion capture that they filmed with a mocap actor. While Bernard says the mocap performer did a great job, a lot of her expression was through her face, which they had to replace for Cosmo with body pantomime (09:37-10:09).

Herman: A Body Size for Every Job

Digital Domain made the main four-foot and twenty-foot tall versions of the loud, sarcastic, and confident Herman (11:31-15:06), while ILM took those models and made the superlative sixty-foot and eight-inch versions.

Herman was built to lift and move things, so Digital Domain focused on making his robust joints and pistons look like they were functional and really able to carry the weight they did (12:12-12:30).

Herman’s pixelated face is his most unusual feature (12:31-12:41). Digital Domain made his face a screen, agreeing with the directors to base it on the orange-on-black monochrome computer monitors of the late ’80s and early ’90s (12:47-13:22).

“Their pixels don’t actually turn on and off instantly,” Bernard says. “They do this crossfading thing from one shape to another… So, we developed this staccato style of facial animation where we would land on an expression and hold it for a beat before going on to the next one to keep things looking crisp and period-specific to the tech of that time [13:23-13:48].”

They developed a library of about 60 expressive shapes for Herman’s face, which they shared with ILM. Then Digital Domain’s rigging team went a step further by creating a custom Maya plugin that let them control every pixel in Herman’s 80×80 grid that made up his face. They could even project images and animations onto his face. That ability was used sparingly, for example during a moment that was cut out of the film when the classic video game Pong played on Herman’s face to show when he was bored. You can see a short clip of the Herman face projection in the video (14:59-15:06).

The Marshall: Bot-Killer

In The Electric State, the Drones are mass-produced robotic shells operated by remote humans, with the human operator’s face projected through the Drone’s head (15:41-16:15). Bernard says they were meant to be more like disposable stormtroopers, with a clunky, heavier style of movement intended to feel cold and inhuman.

The Marshall (16:16-18:35), played by Giancarlo Esposito, is an earlier version of the Drone technology and was a key player in the robot wars, where the humans defeated the Bots. The mocap performer for The Marshall played it with “a touch of cowboy swagger,” Bernard says, with stiffer joints and a range of motion limited by rust and disrepair. This complemented Esposito’s delivery, which had a quiet and dignified professionalism.

“Even though his drone was a built-to-task bot-killing machine, when we animated him, we were looking for a balance between those two things,” she says. “The restraint of the man behind the drone and the strength and the ruthless violence he was capable of delivering with that drone body.”

Digital Domain developed four different movement styles for each of the main characters to pitch to the directors. For The Marshall, these styles ranged from smooth and natural to stiff and clunky (17:26-18:35). The directors wanted something right in the middle. “The nice thing about doing that motion exploration early in the process is that early effort gave us concrete answers for how those main characters should move, and also a shared language for the rest of the minor characters later.”

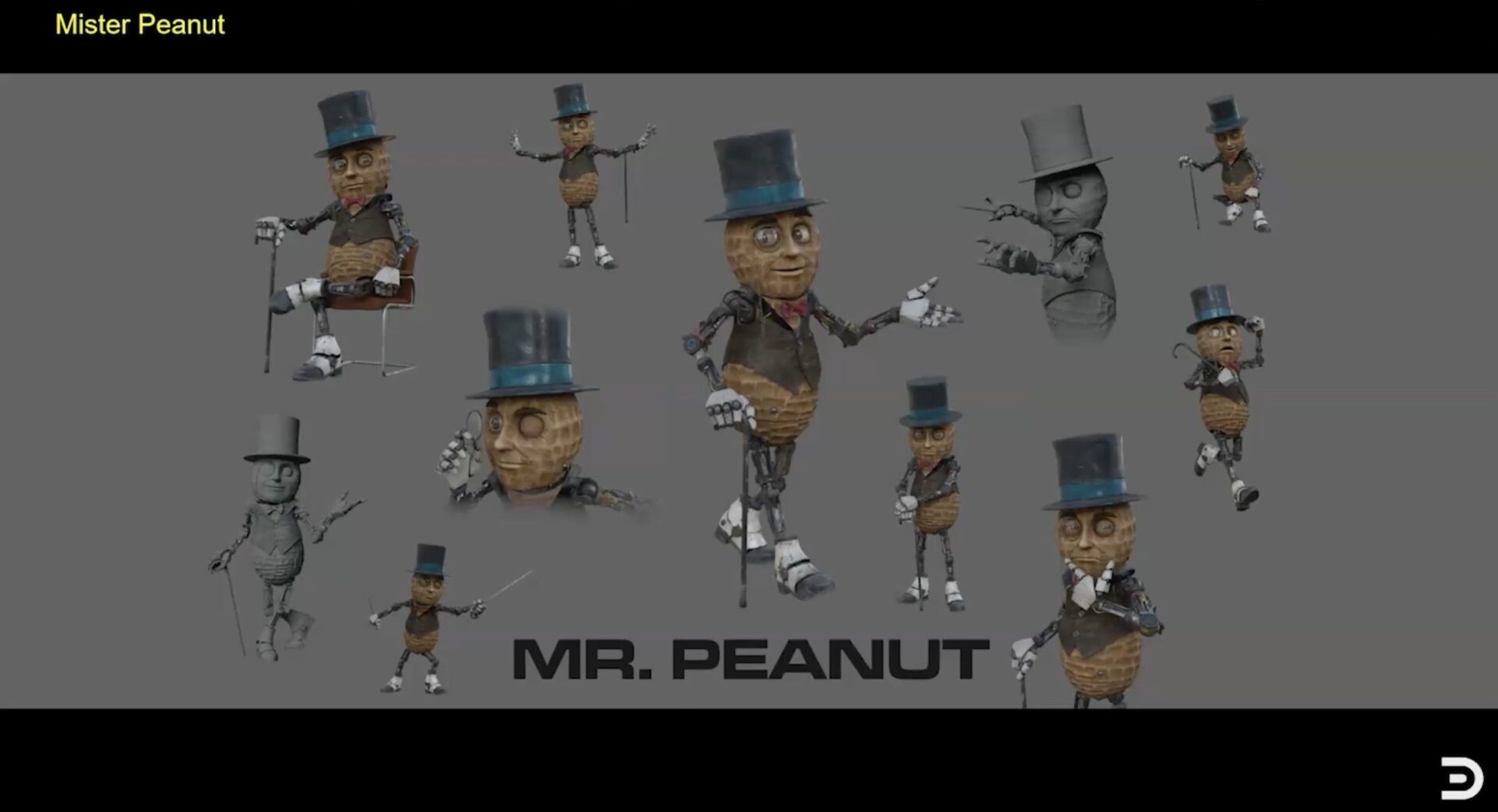

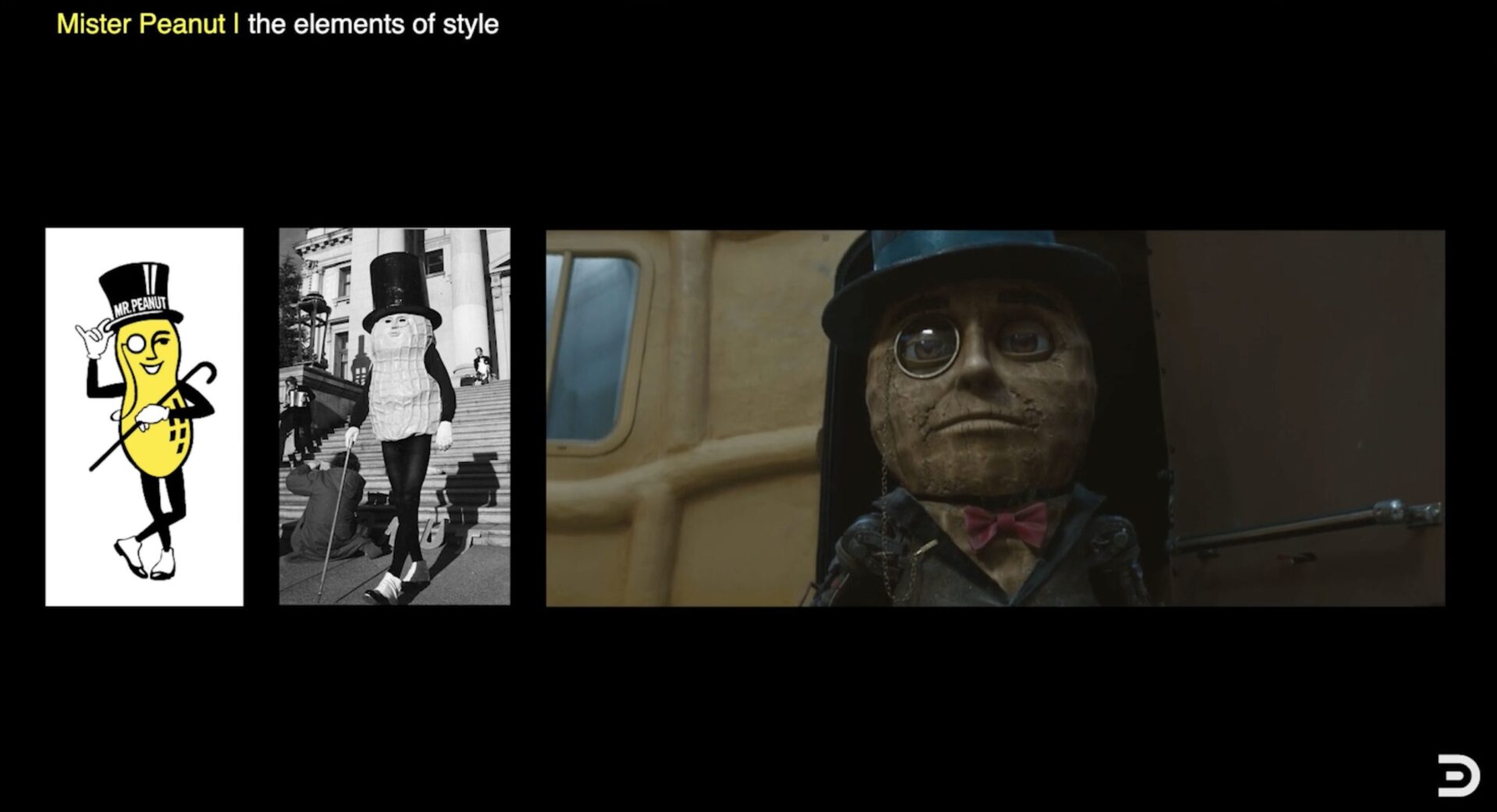

Mr. Peanut: The Elder Statesman

Yes, he’s that Mr. Peanut. As the only character in The Electric State based on a real world character, in this case a corporate mascot, Bernard says he was the most challenging character to develop. For one thing, because of the dual writers and actor strikes of 2023, they had to animate a bunch of shots without knowing who would voice Mr. Peanut, which required reanimating many of those same shots after Woody Harrelson was cast.

Also, Digital Domain had to keep certain identifying aspects of the corporate mascot, like the top hat, monocle, and cane. But if they kept the original character’s solid peanut shell, the animated character’s body would be too stiff to move (19:29-19:58). So, the first thing they did was “chopped off his head” and gave him an articulated neck so he could nod, shake his head and look in different directions. “In a further indignity, we sliced off his butt so we could swivel it like hips,” Bernard says. “His walk would still be pretty stiff [19:59-20:57], but it was kind of perfect for his history as a war veteran and the elderly warble that Woody had given his voice.”

Harrelson’s Mr. Peanut vocal performance also leant a lot of gravitas to the leader and savvy politician who had founded a desert oasis of Bot safety in The Electric State. “You know what they say, the eyes are the window into the soul,” Bernard says, “and we knew from Woody’s vocal performance that this character had a lot of soul.”

Digital Domain spent a lot of time on Mr. Peanut’s eyes (20:58-22:02), making their animations fundamentally human: long, thoughtful gazes; quick, fearful eye darts; and well-timed comedic blinks. For Mr. Peanut’s mouth (22:31-22:52), they steered clear of too much articulation in the lips to avoid looking cartoonish, worried that he would not fit with the gritty world of the other bots if the lips went too rubbery or human. After lots of trial and error, they reduced the blend shapes for Mr. Peanut’s mouth from over eighty down to a sweet spot of around six. “Less is sometimes a whole lot more,” Bernard says.

The Mall: Lots o’ Bots, Little Simulation

Of the more than 100 unique characters created for The Electric State, the contributing VFX studios collaborated to make 80-90 of them just for the big reveal of the Mall, Mr. Peanut’s Bot safe haven in the desert (24:20-24:39). These included tire bots, “pill bots,” a giant walking donut, and among many others, Perplexo, magician extraordinaire, voiced by Hank Azaria of The Simpsons fame (23:18-23:57).

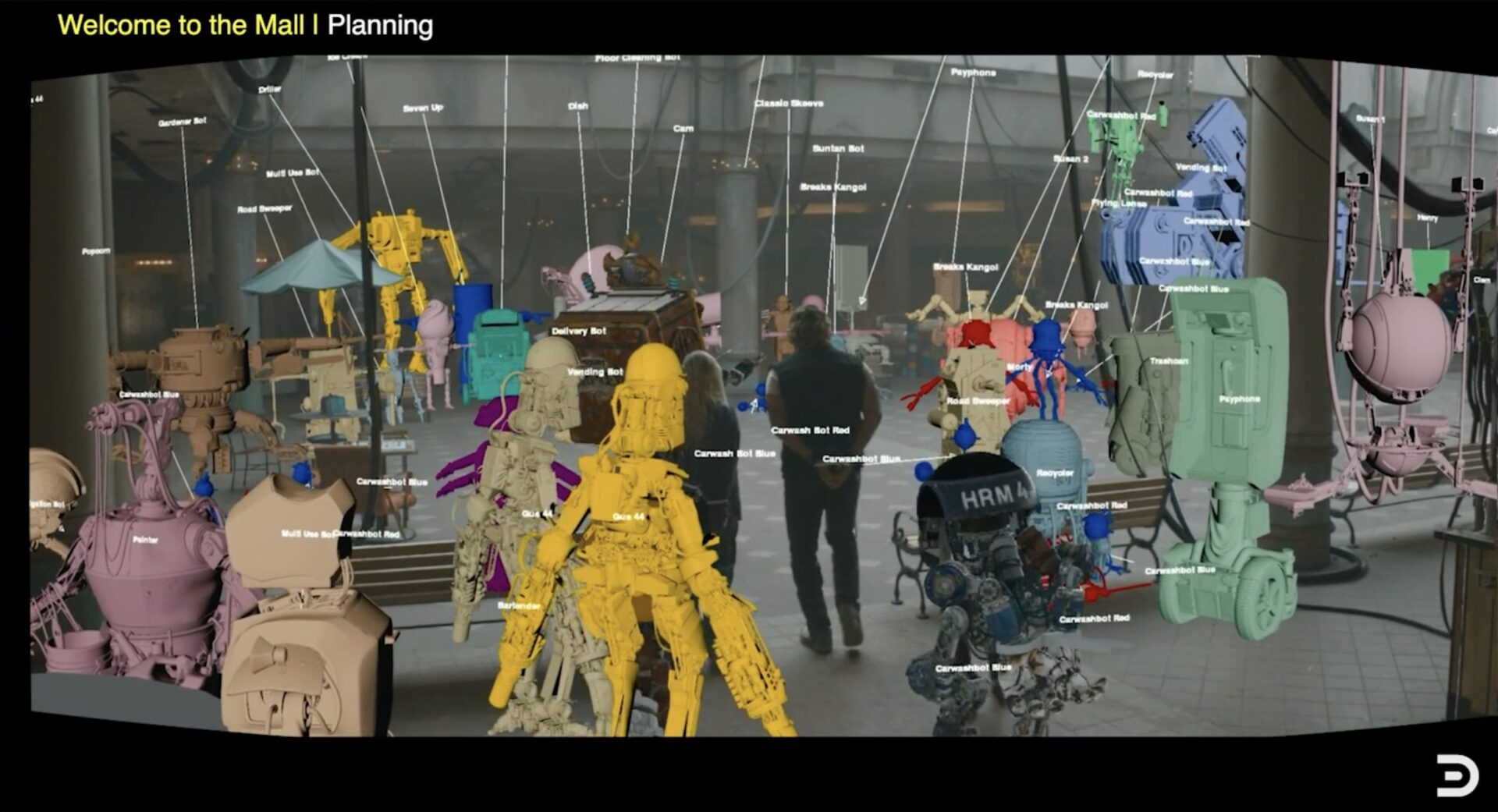

To approach the complicated arrangement of so many Bot characters in the Mall’s interior, Bernard says they started with a “chess piece layout” to plan and manage all the different placements, movements, colors and sizes of the animated characters.

Then she says the real work started by producing a playblast of an epic shot of the heroes first encountering the interior world of the Mall, which you can see in the video (24:40- 27:10). Unlike many 3D character crowd scenes, where you have similar repeating characters you can run through Golaem for Maya to simulate crowds, 90% of the characters in these scenes were not simulated or automated. They all had different body types and movements and needed their own custom hand key framed animation.

Bernard notes that they used Golaem for the hazy far backgrounds of these shots. For that they created three generic bot rigs with head and body variants for their crowds team to randomize.

“I assigned each animator on my team to two or three different bots and gave them carte blanche to animate them how they wanted… as long as it made sense with the character’s body type and the style of the film,” she says. “This was super fun… seeing all these ideas, jokes, gags, and insights coming through each one of the animators’ clips. They all put their own personality into these bots. We got this very organic mix of styles and distinct characters. When we assembled all of that human generated work… it was really magical.”

Happyland: Scavenger Bots and Golaem Crowds

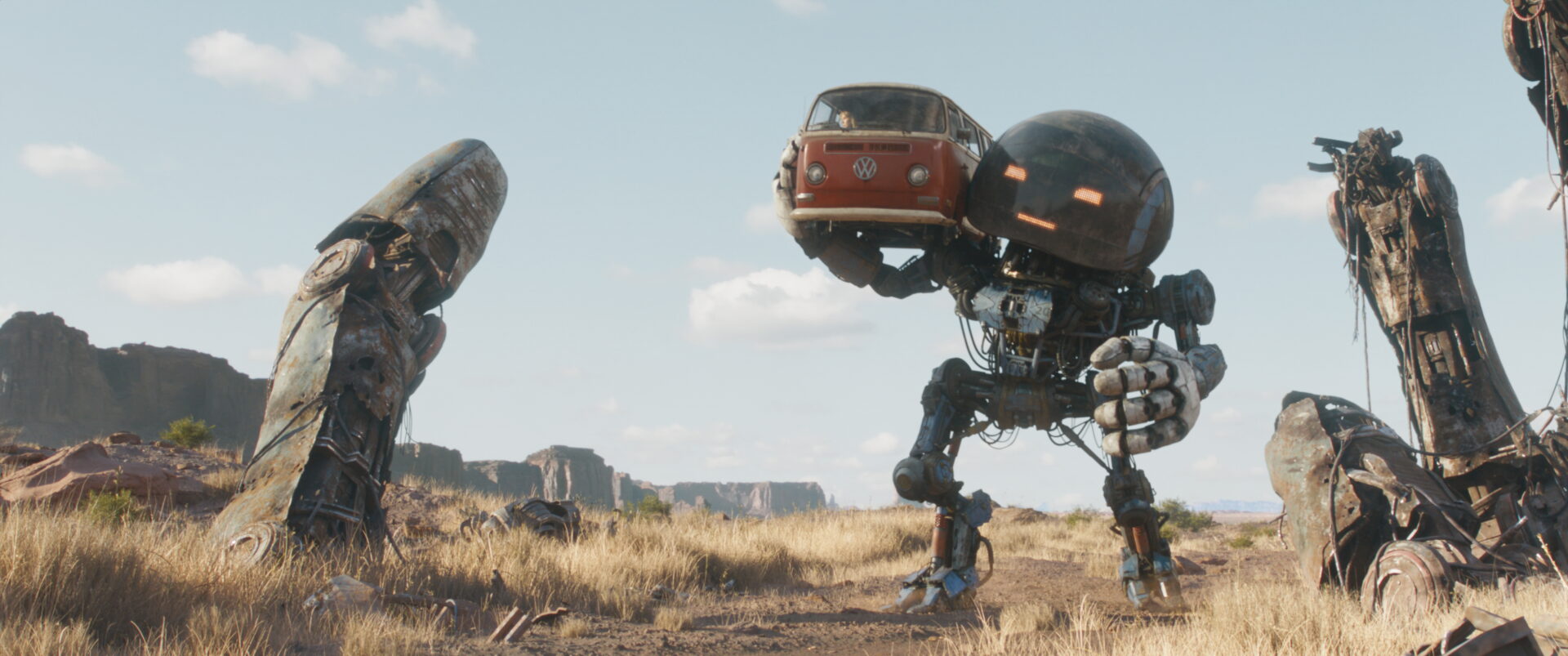

Outside of the haven of the Mall, The Electric State’s heroes were in constant peril of meeting up with scavenger bots, or “scavs,” which build and repair themselves out of whatever they can scavenge in the desert (27:38-28:22).

And when they make it to Happyland, a sort of haunted amusement park (28:24-29:12) they run into hordes of zombie-like robots. Here’s where Digital Domain flexed its crowd character development muscles using Golaem for crowd simulation, giving the sense that Michelle and her gang of misfits were completely surrounded.

“Happyland is one of the places in the film where we used a lot of Golaem generated crowd simulation to help fill out shots and give the sense that there was a horde.”

Digital Domain’s rigging team created some generic scavenger bot rigs with swappable body parts and the crowds artists randomized them in Golaem, so the audience would never see the same background bot twice. Thus closes the book on The Electric State for Digital Domain, which has since worked on such films as The Fantastic Four: First Steps and The Conjuring: Last Rites. “This was an absolutely huge show for us,” Bernard says. “We’re all really proud of how it turned out.”

Watch the full recording of Liz Bernard’s presentation on The Electric State here. See more of Digital Domain’s work on the project here.